8 Geometric Properties

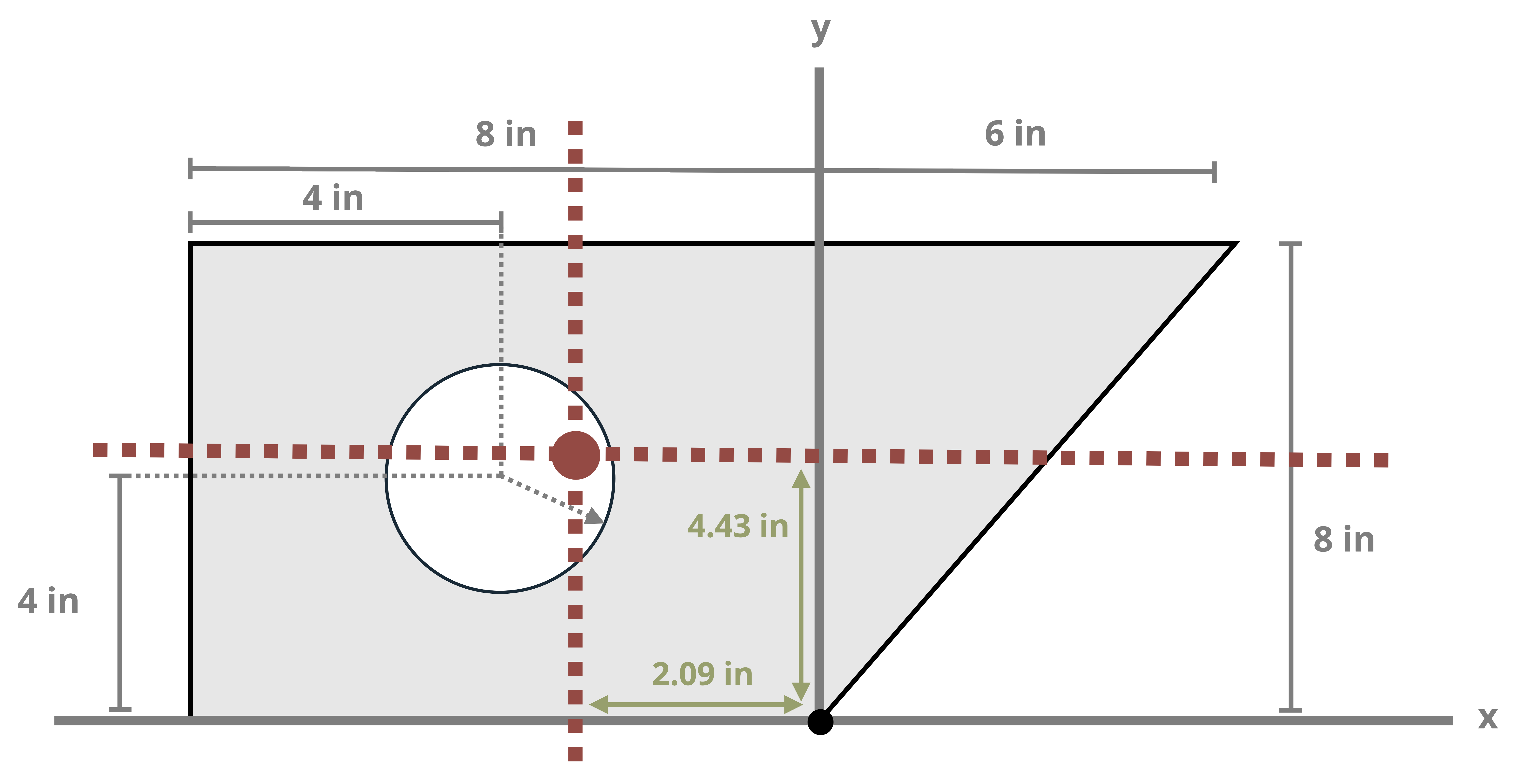

As previous chapters have shown, geometric cross-section properties are critical to calculating stresses and deformations for members subjected to axial and torsional loads. The same is true for finding stresses and deflections in beams subjected to shear and bending loads. This chapter describes methods for finding section properties necessary to calculate the stress and deflection in beams—specifically, the centroid and the second moment of area (also known as moment of inertia and area moment of inertia).

You likely were presented with these topics in statics, so this chapter is designed to be a review. Section 8.1 reviews centroids, and Section 8.2 reviews second moment of area.

.jpeg)

8.1 Centroid

Click to expand

An object possesses weight as a result of the gravitational force acting on its constituent particles. The collective effect of these forces yields the total weight of the object, which is concentrated at a single point known as the center of gravity. If the object is composed of a homogenous (constant density) material, then the center of gravity is the same as the geometric center or centroid.

The discussion in this section focuses on the centroid of an area for common structural shapes. For a more comprehensive discussion on the center of gravity, the center of mass, calculating centroids using integration, and distributed loads, see the book Engineering Statics by Baker and Haynes.

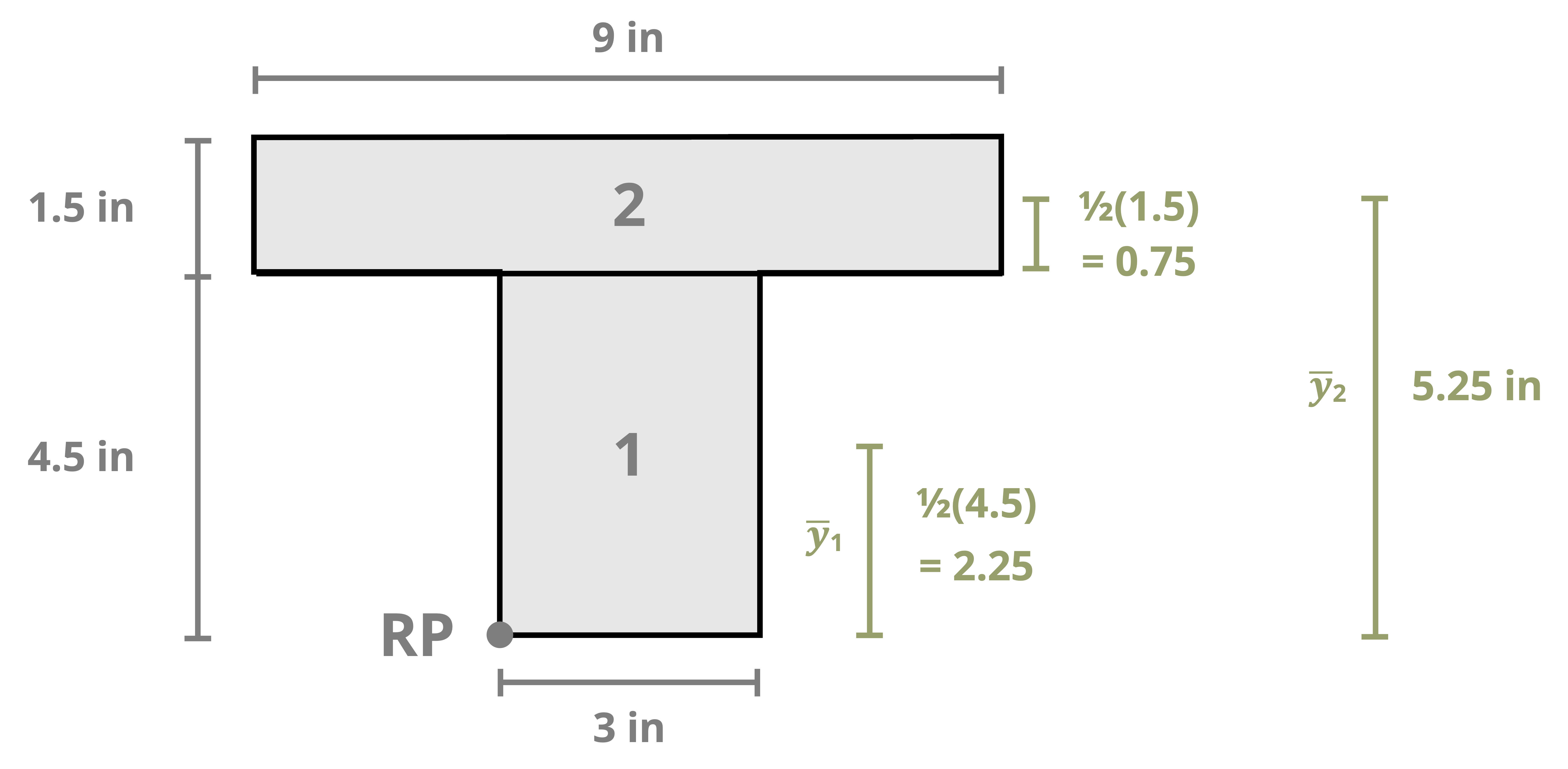

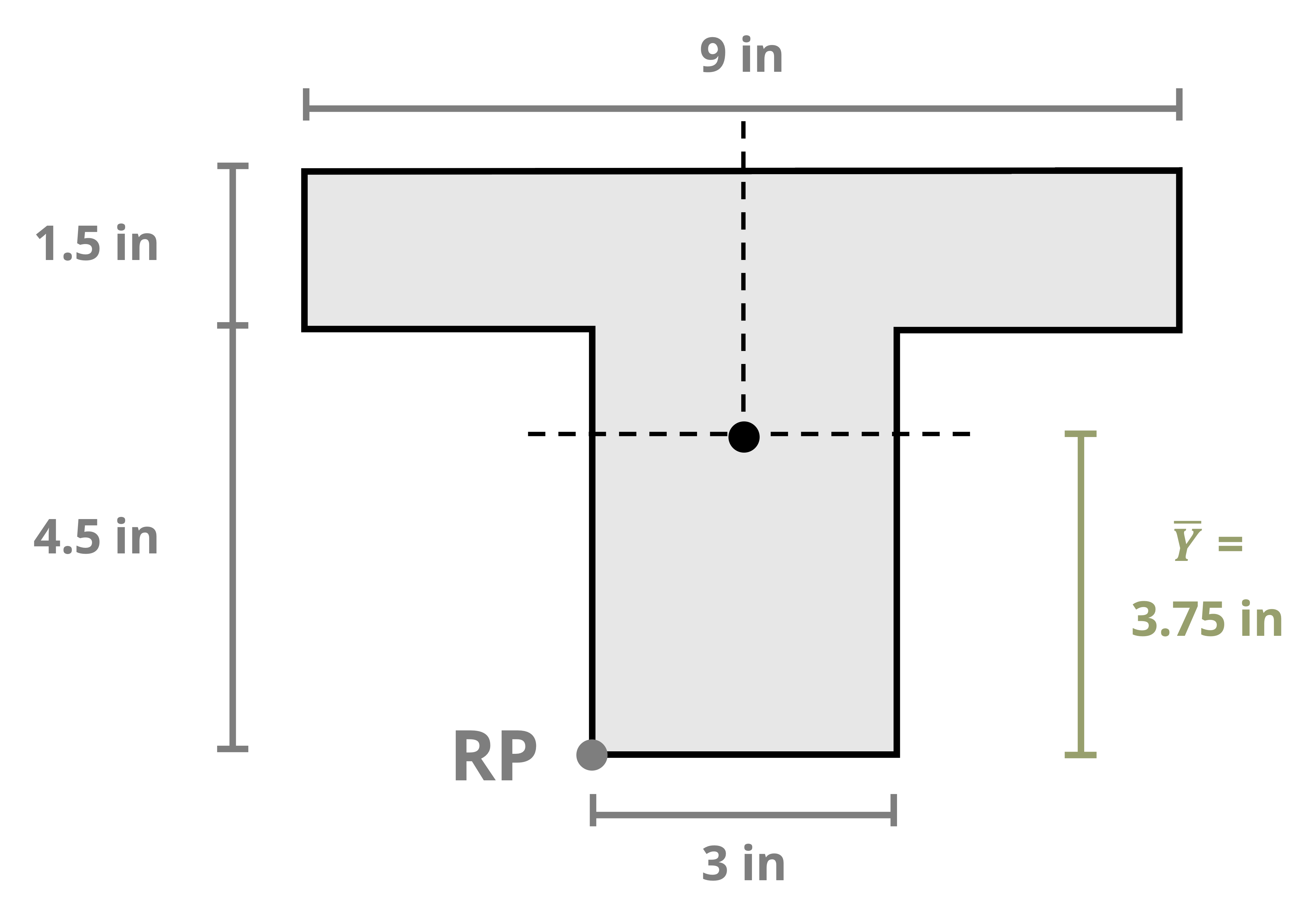

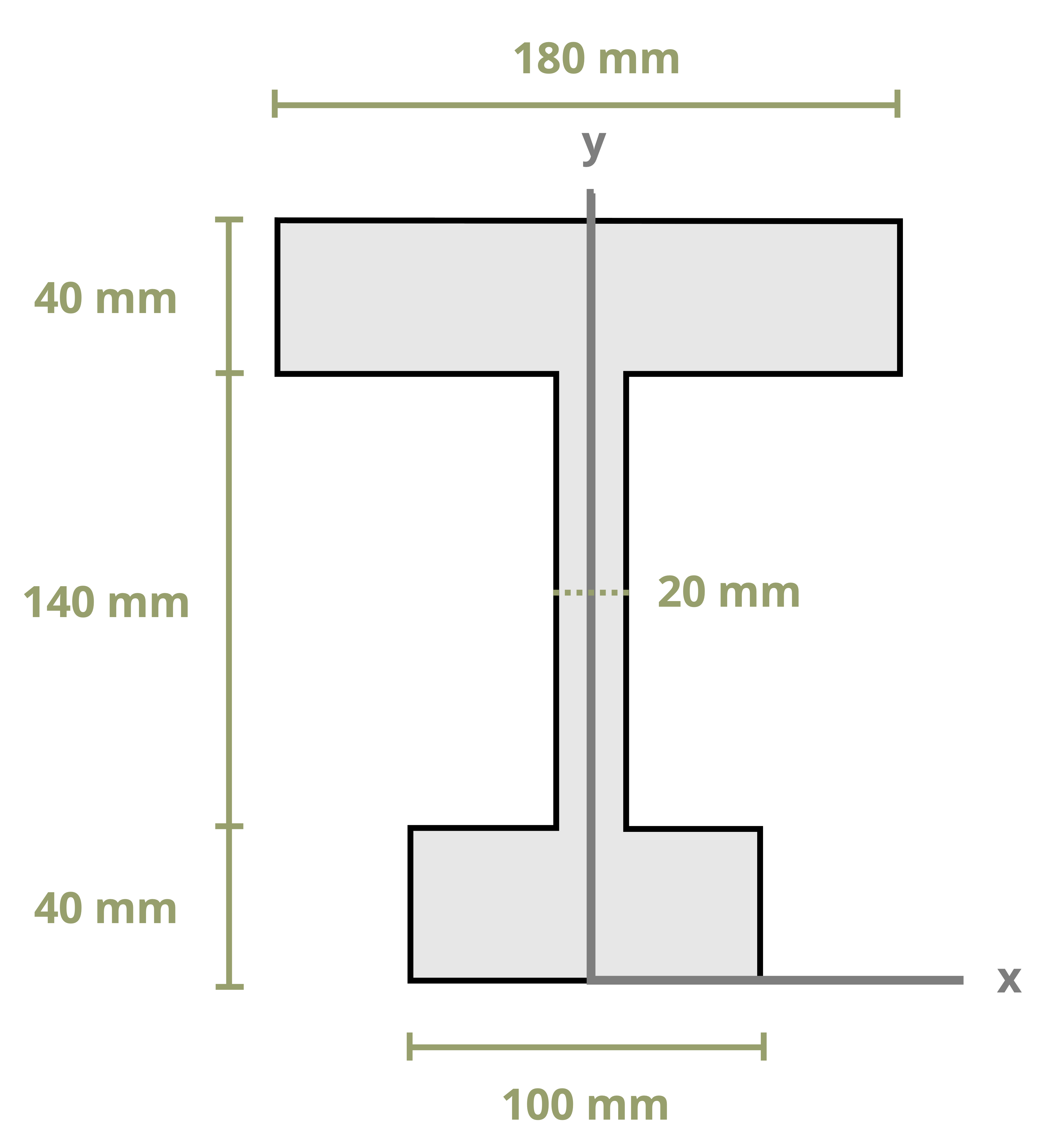

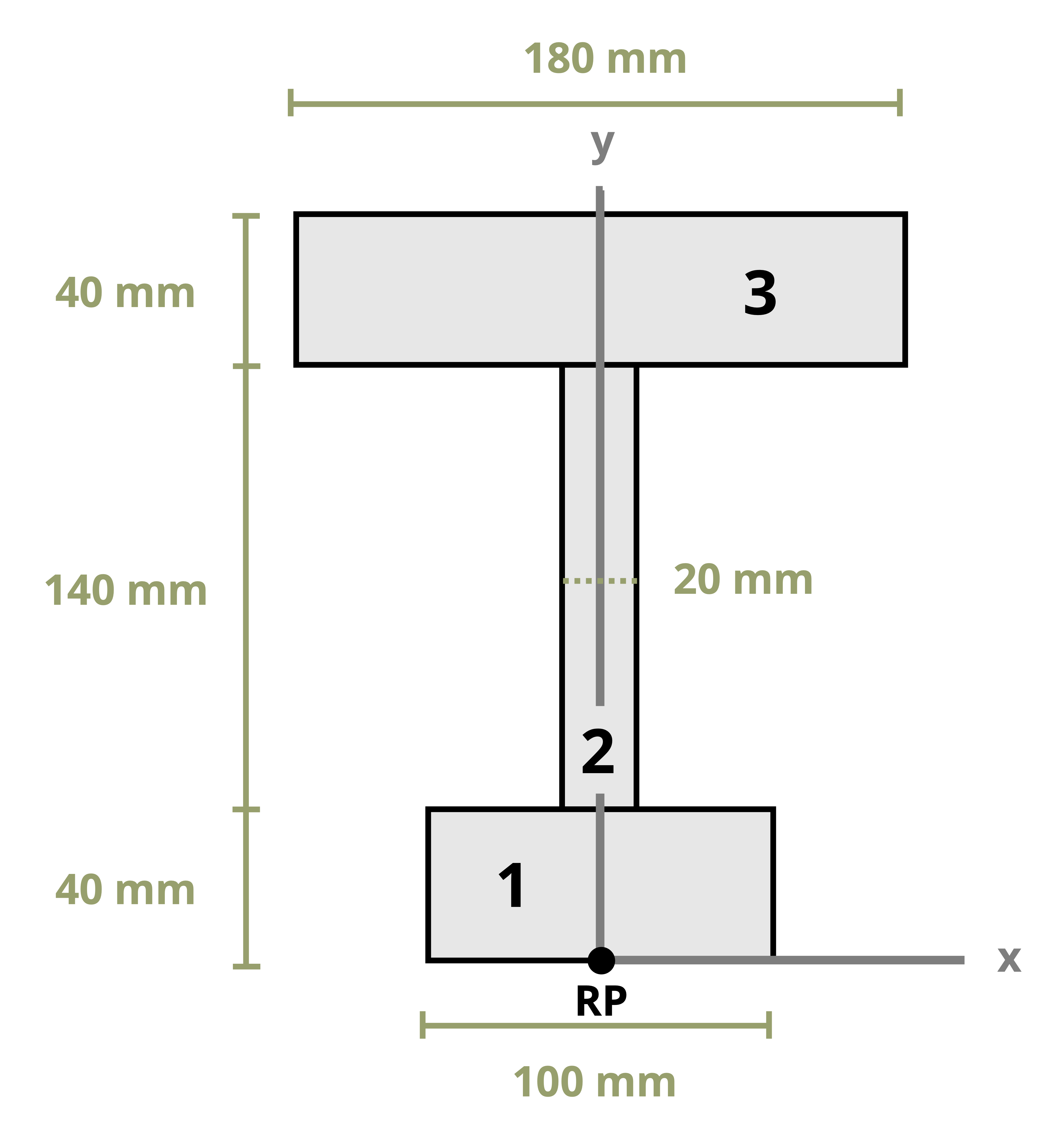

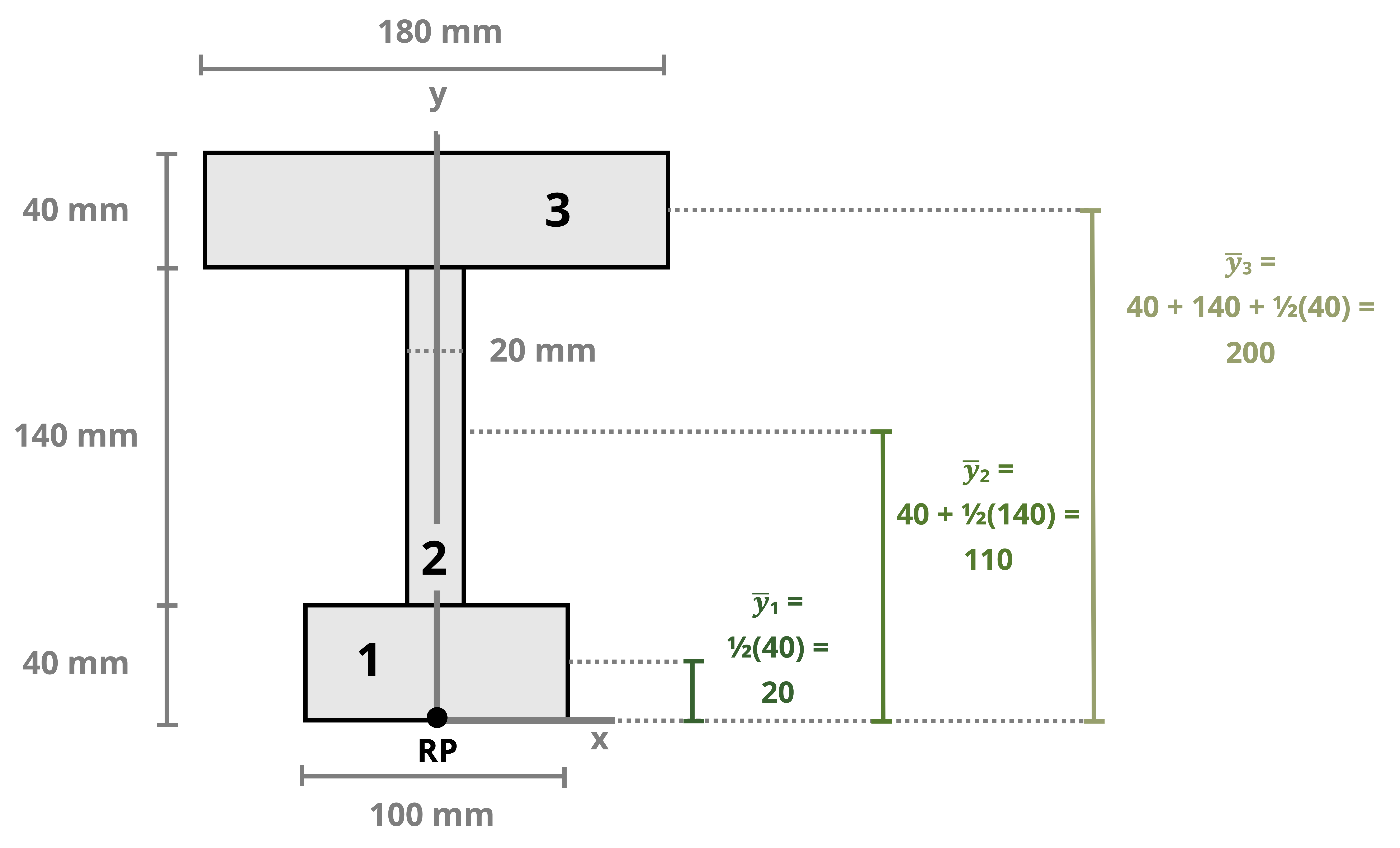

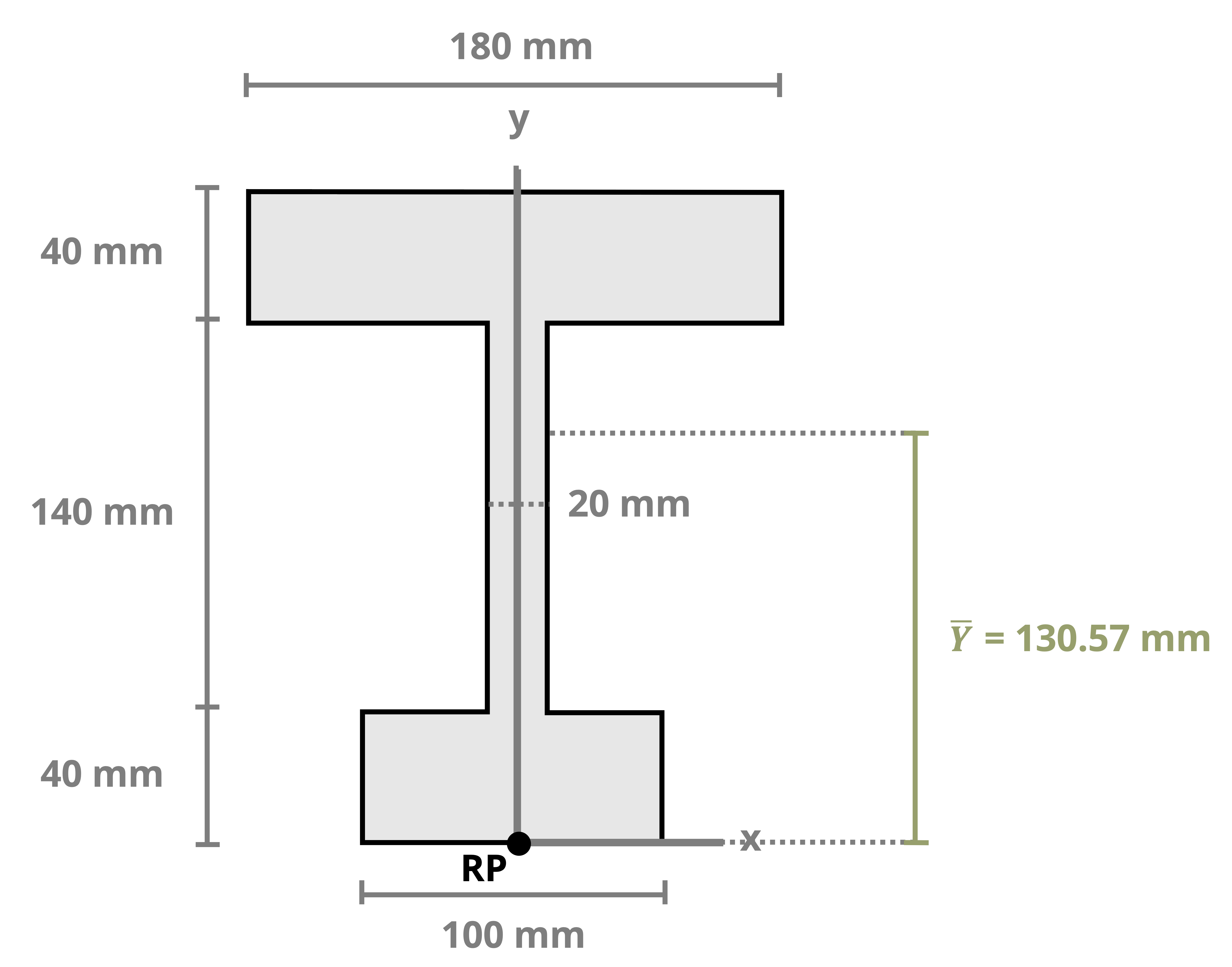

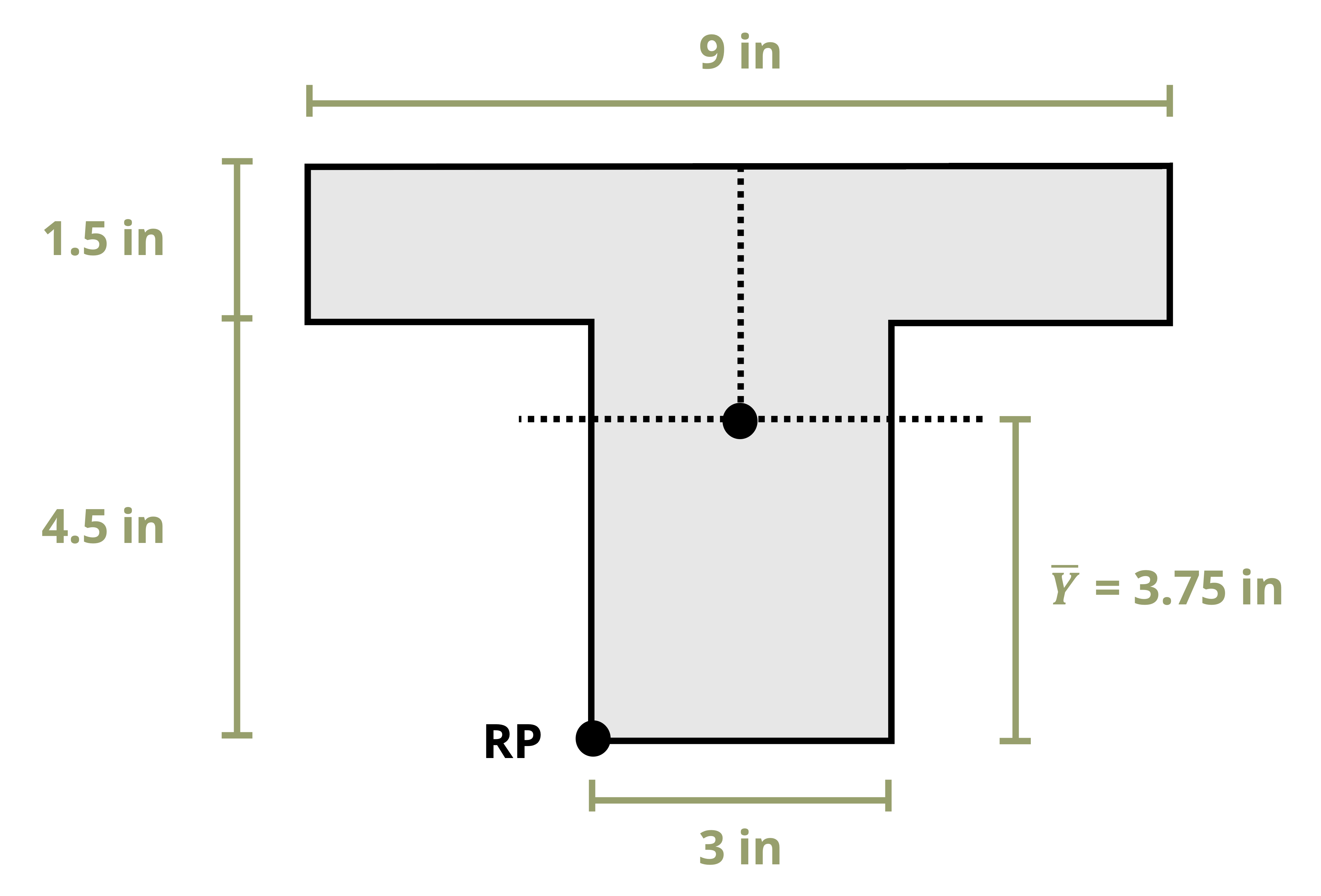

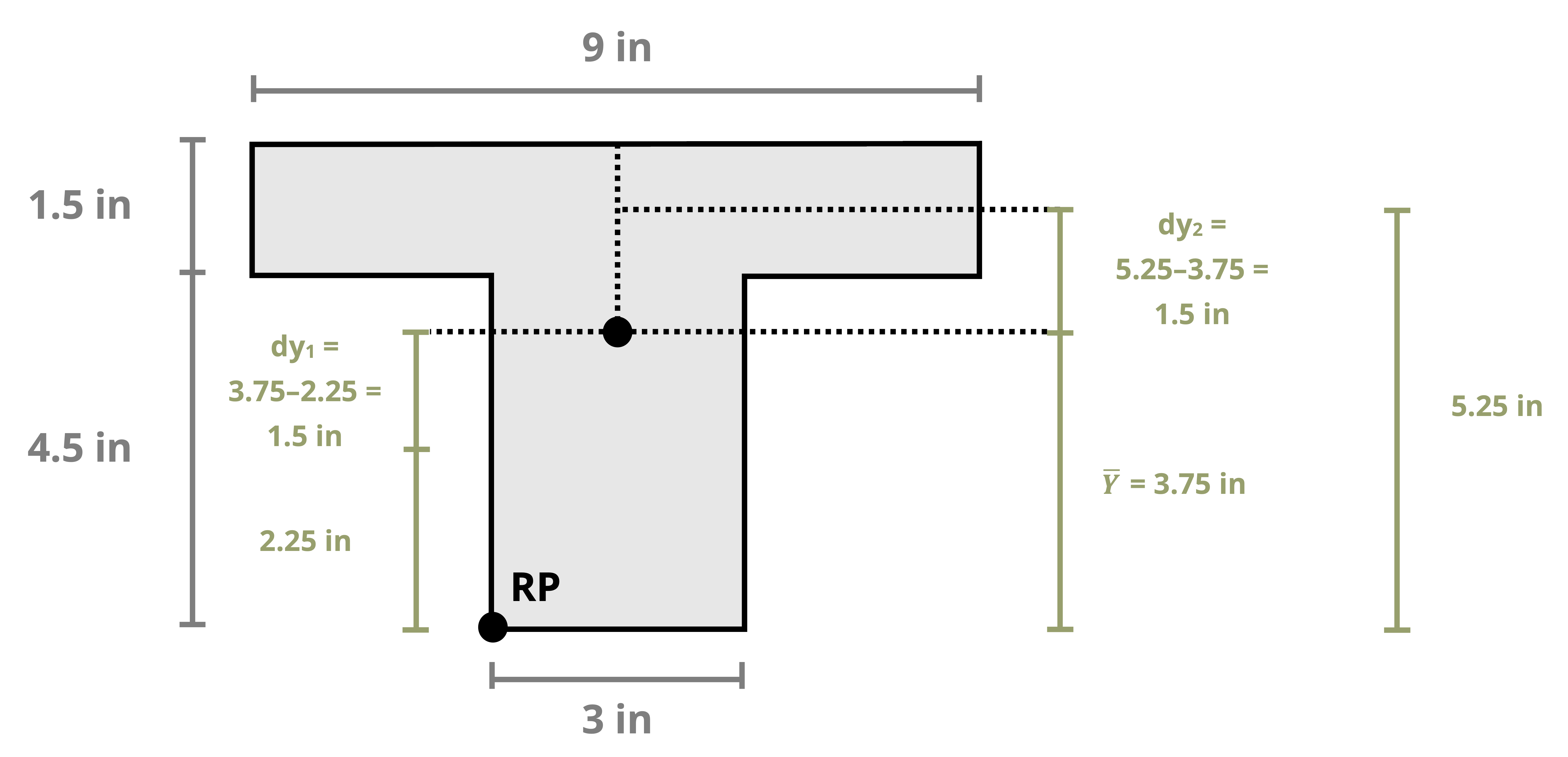

The location of the centroid of an area is the point where the first moment of area equals zero. The first moment of area about a point is calculated by multiplying the area by the perpendicular distance to the point. The centroid of an area can be found by splitting the area into a number (i) of discrete parts, summing the moment of area for these discrete parts, and then dividing by the sum of the area. These weighted averages enable us to find the location \((\bar{X}, \bar{Y})\) of the centroid of the area.

\[ \boxed{\begin{aligned} &\bar{X}=\frac{\sum \bar{x}_i A_i}{\sum A_i} \\ \\ &\bar{Y}=\frac{\sum \bar{y}_i A_i}{\sum A_i} \end{aligned}}\text{ ,} \tag{8.1}\]

\(\bar{X}, \bar{Y}\) = Centroid coordinates of the overall area [m, in.]

\(\bar{x}_i, \bar{y}_i\) = Centroid coordinates of each discrete area [m, in.]

\(A_i\) = Area of each discrete area [m2, in.2]

We can find centroids of simple shapes easily by utilizing symmetry. When a shape possesses an axis of symmetry, each point on one side of the axis corresponds to another point symmetrically located on the opposite side. The distances between these mirrored points and the line of symmetry sum to zero because they are equal in magnitude but opposite in sign. This is true for every point in the shape, so the numerator of Equation 8.1 (the first moment of area) will be zero. Therefore, if a shape features a line of symmetry, its centroid must coincide with this line.

In cases where a shape exhibits multiple lines of symmetry, the centroid is located at their intersection, as shown in Figure 8.2.

This text uses common shapes or a composite of common shapes for cross-sections. The location of the centroid of some common shapes can be found in Appendix E, part of which is reproduced in Figure 8.3. Each row of the table includes a common shape with the centroid marked and provides simple formulas for determining the centroid’s x and y coordinates and calculating the area of the shape.

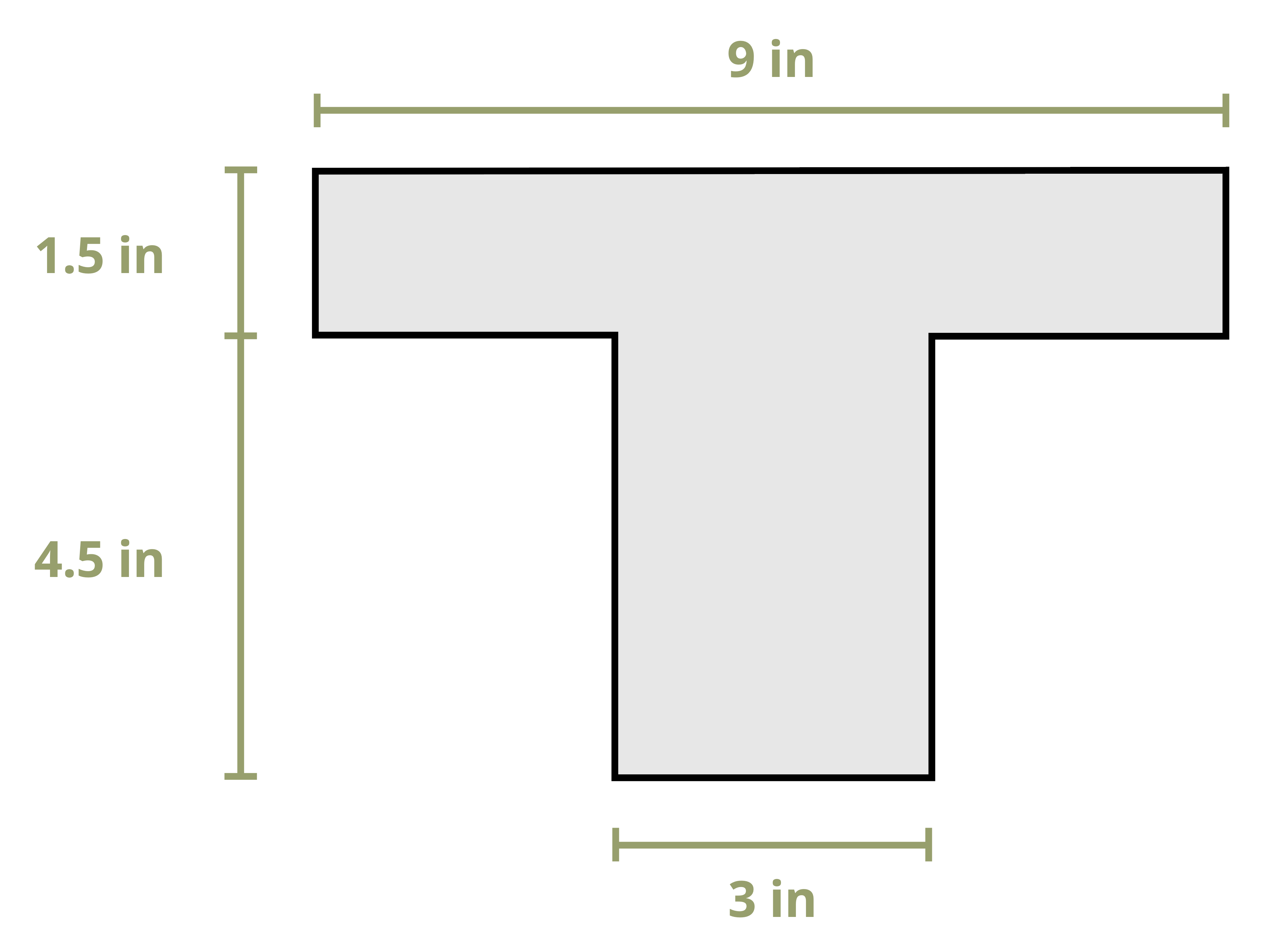

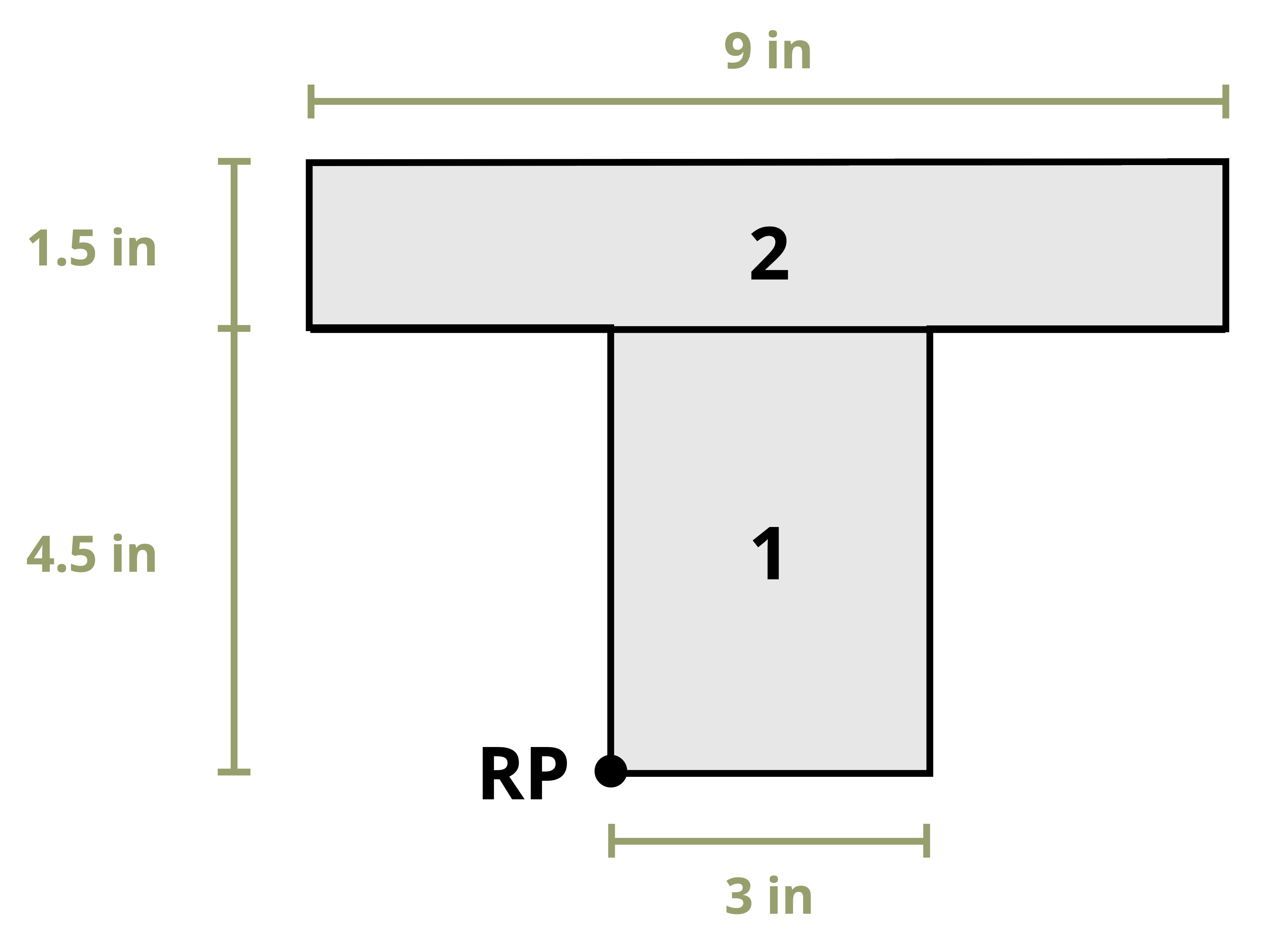

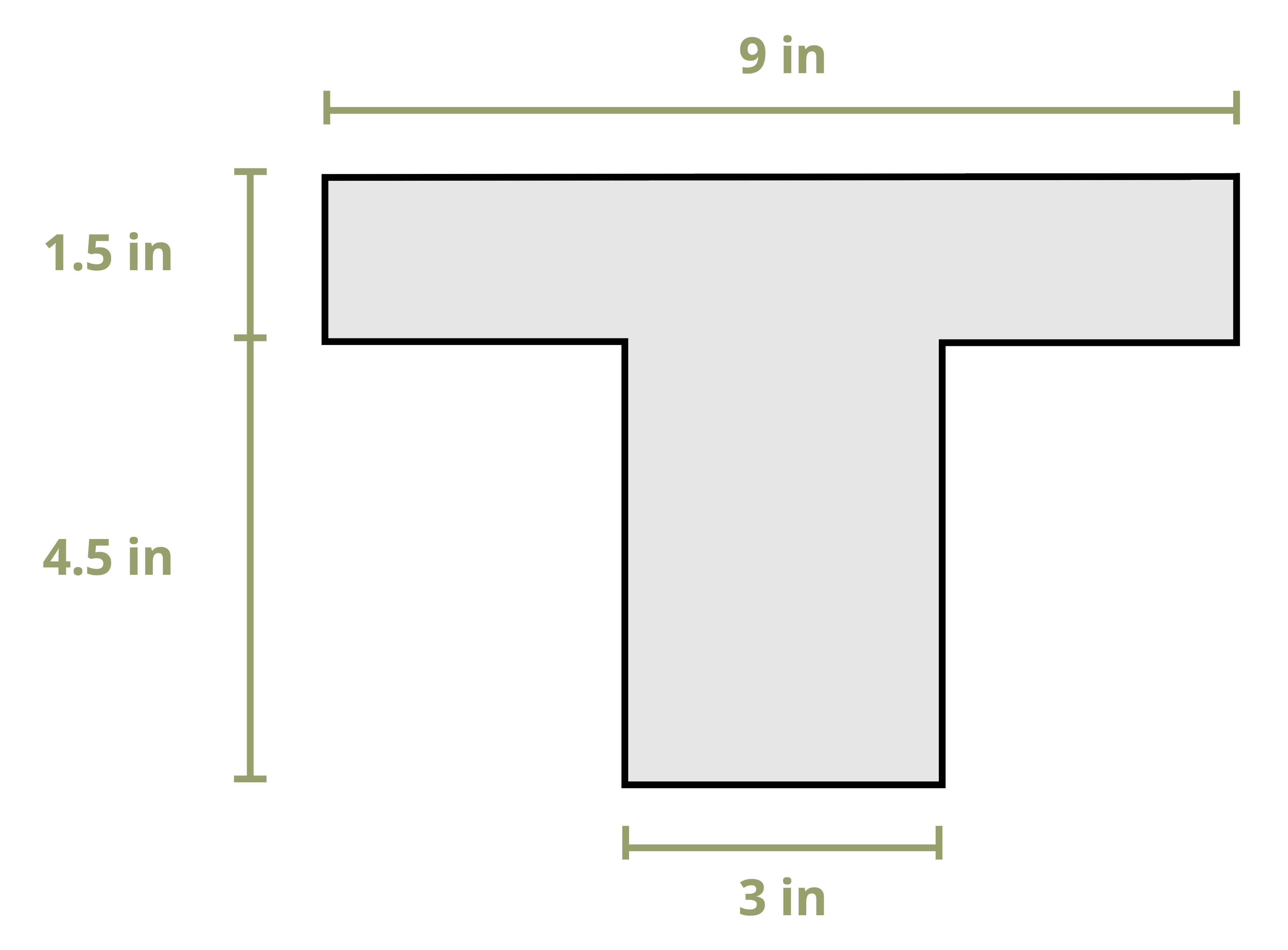

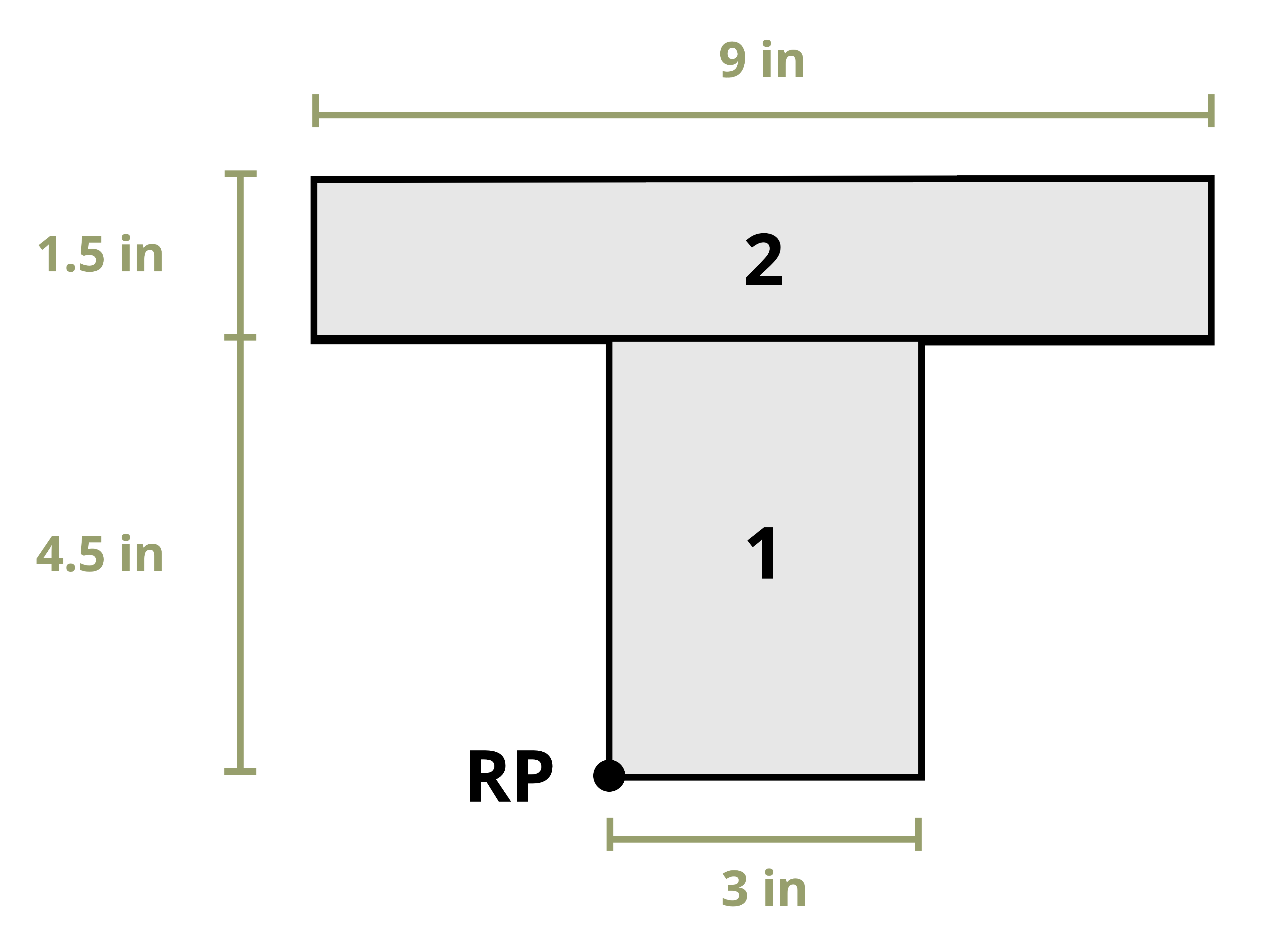

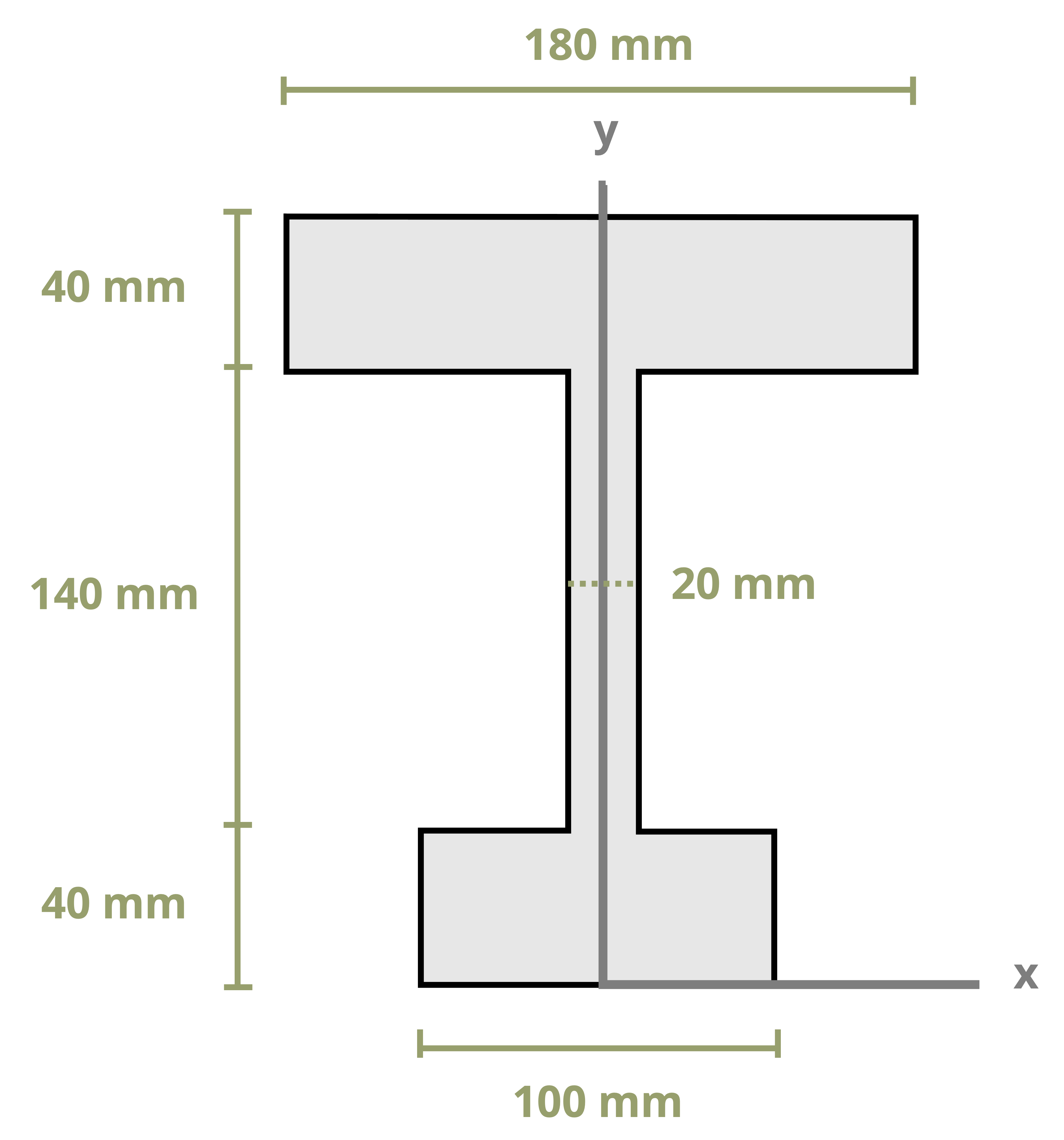

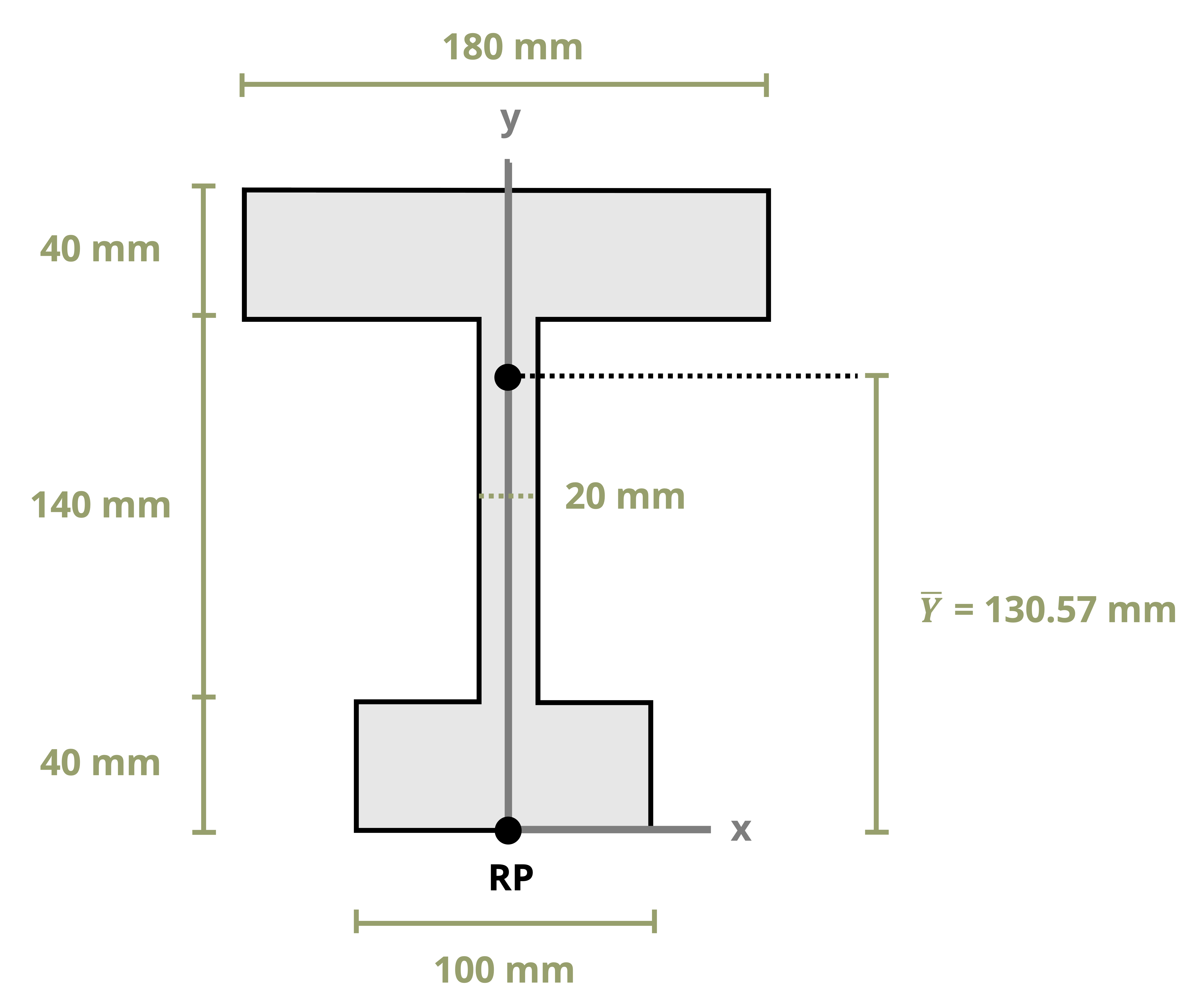

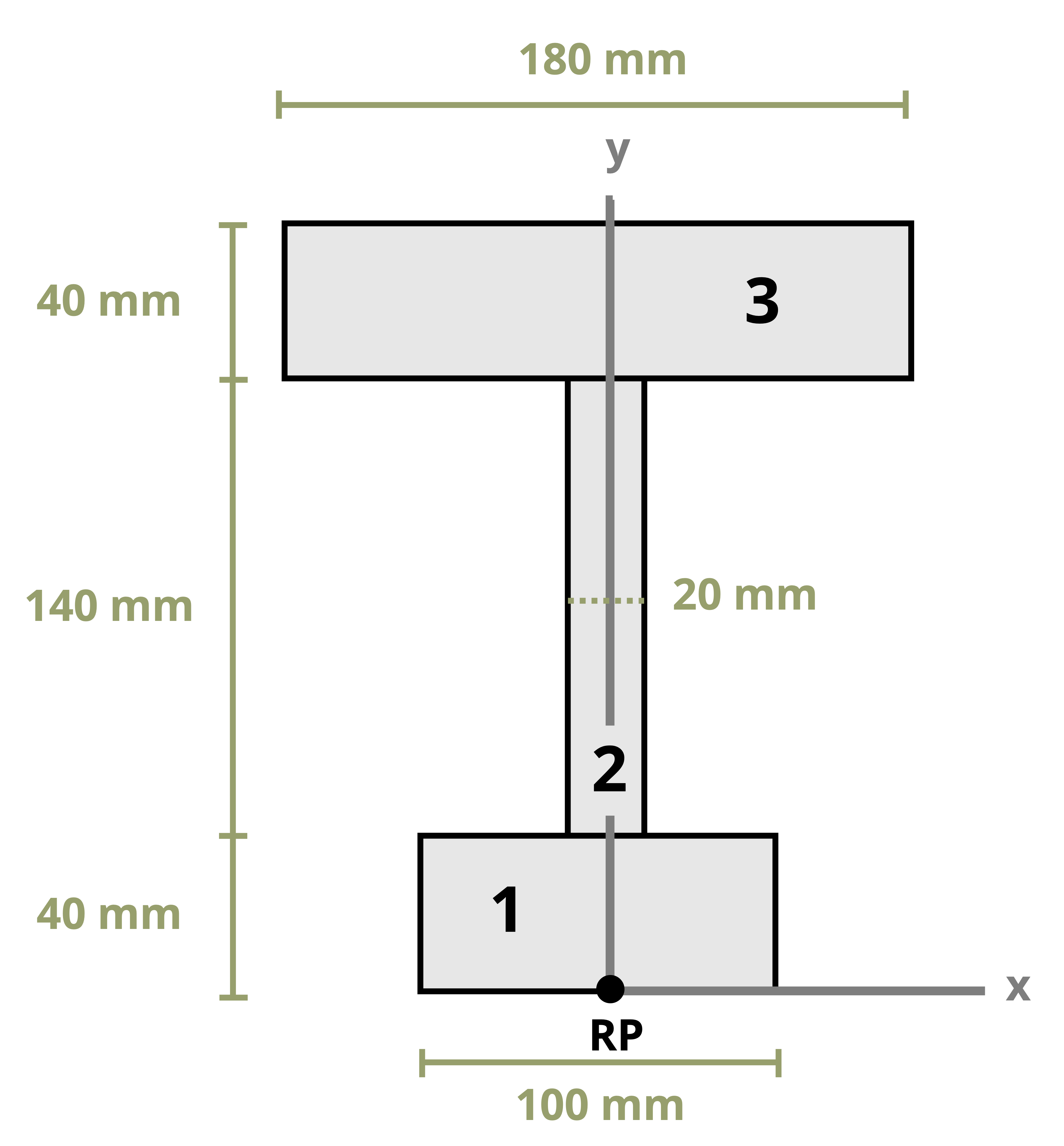

Often structural sections are combinations of these standard shapes. These types of sections are called composite sections. As long as we know the location of the centroid of each shape in the section, we do not need to use integration to find the location of the section’s overall centroid. We can use Equation 8.1 in conjunction with the table in Appendix E to find the location of the centroid for composite shapes.

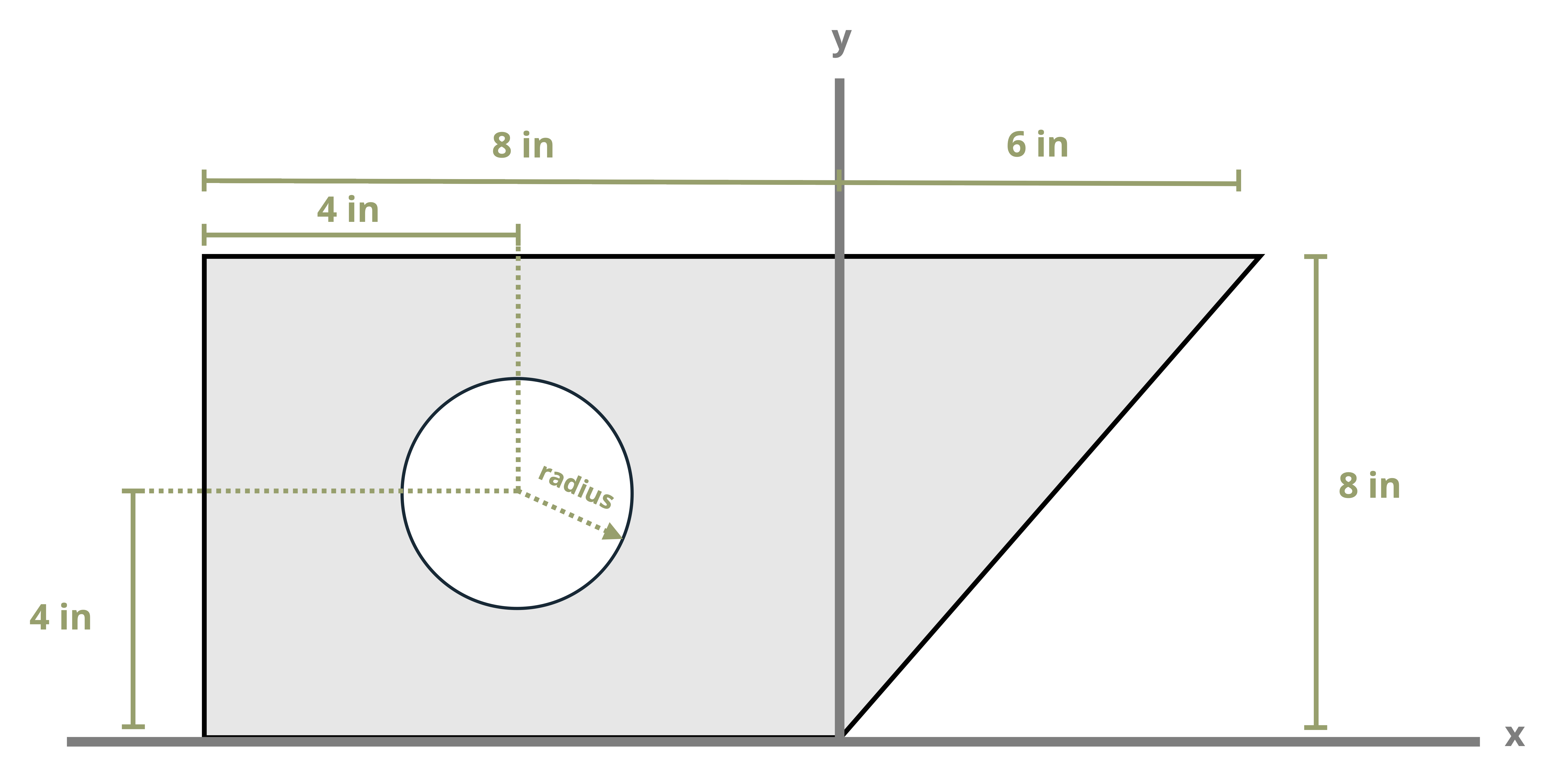

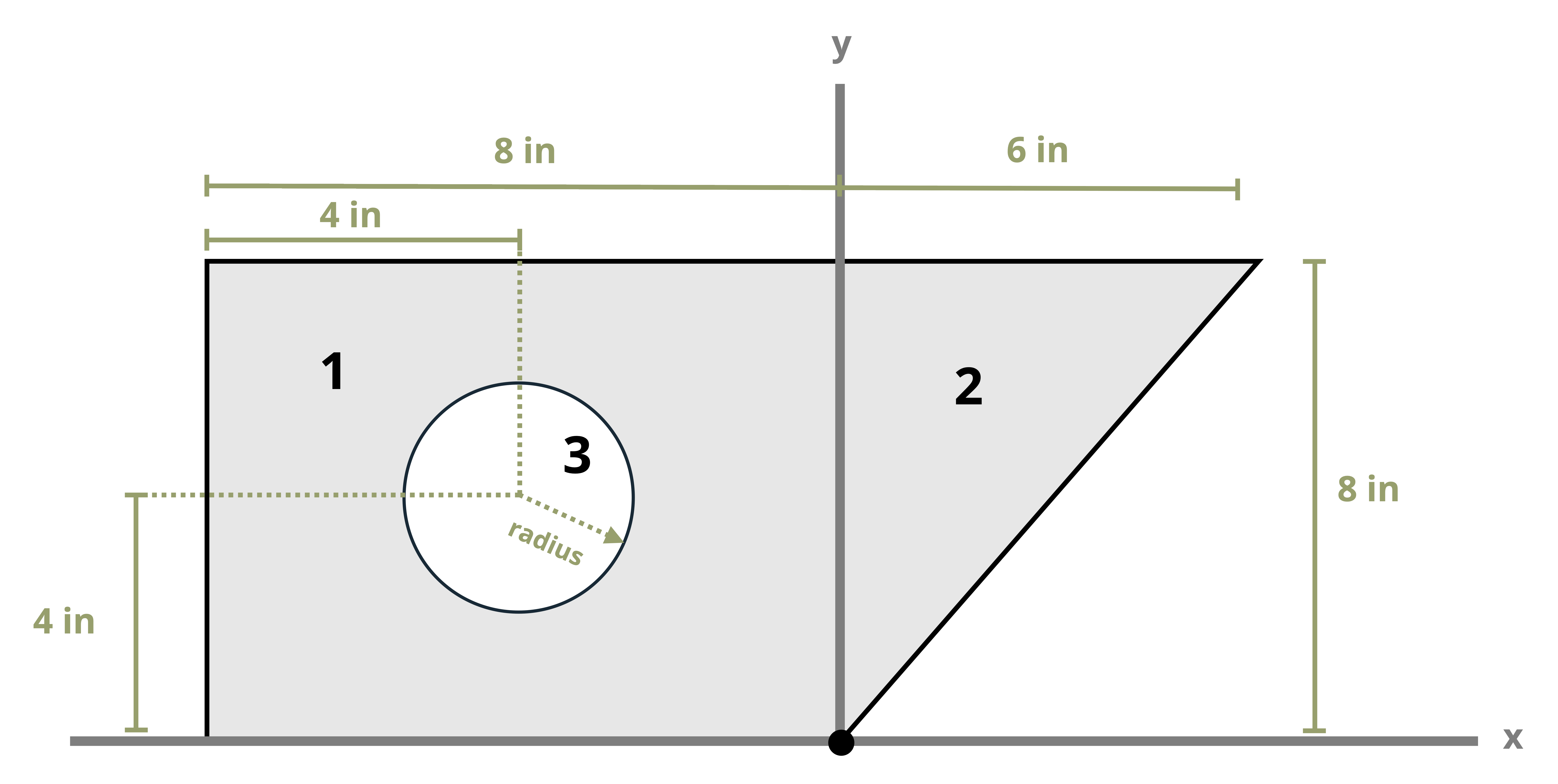

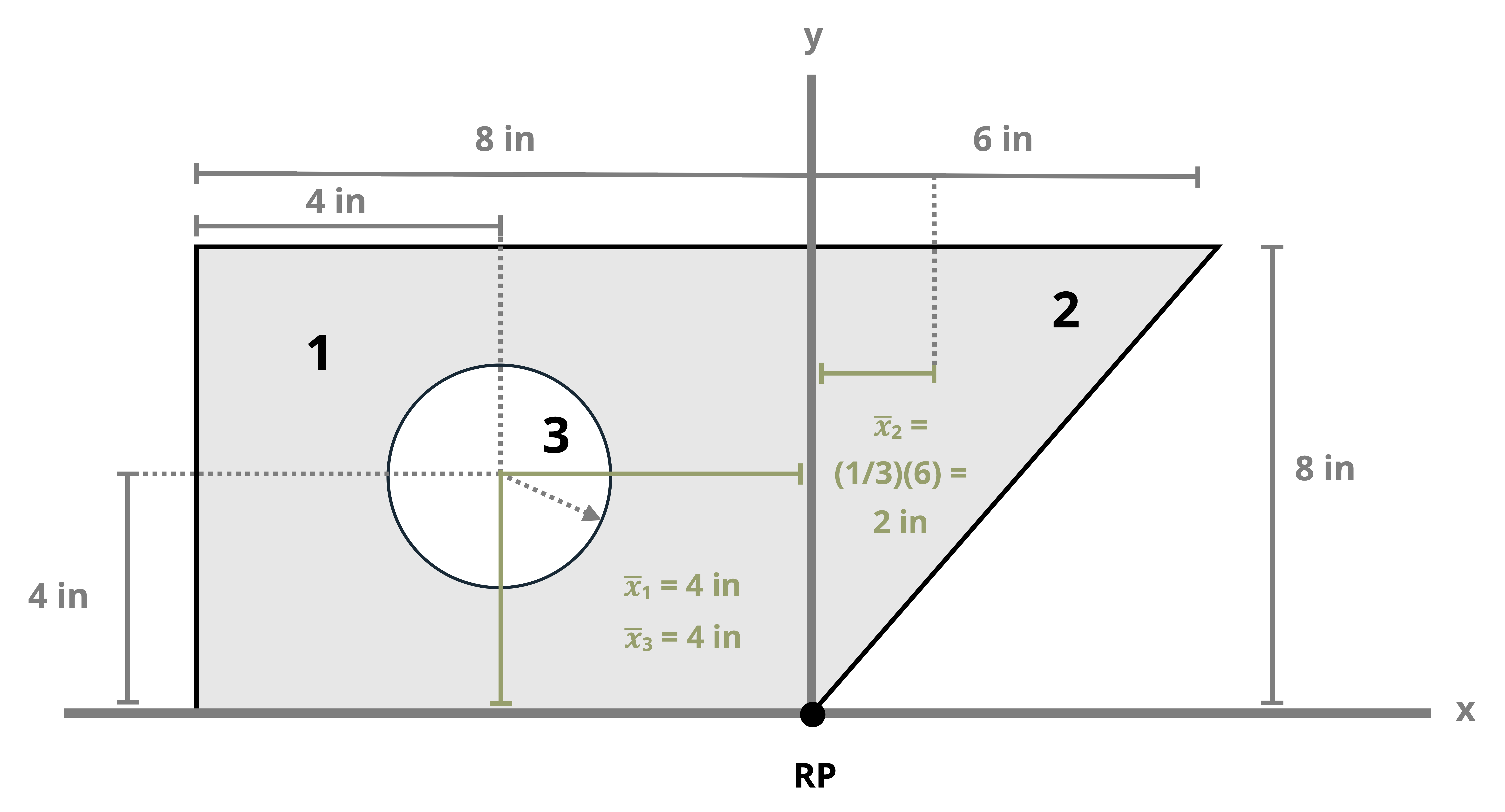

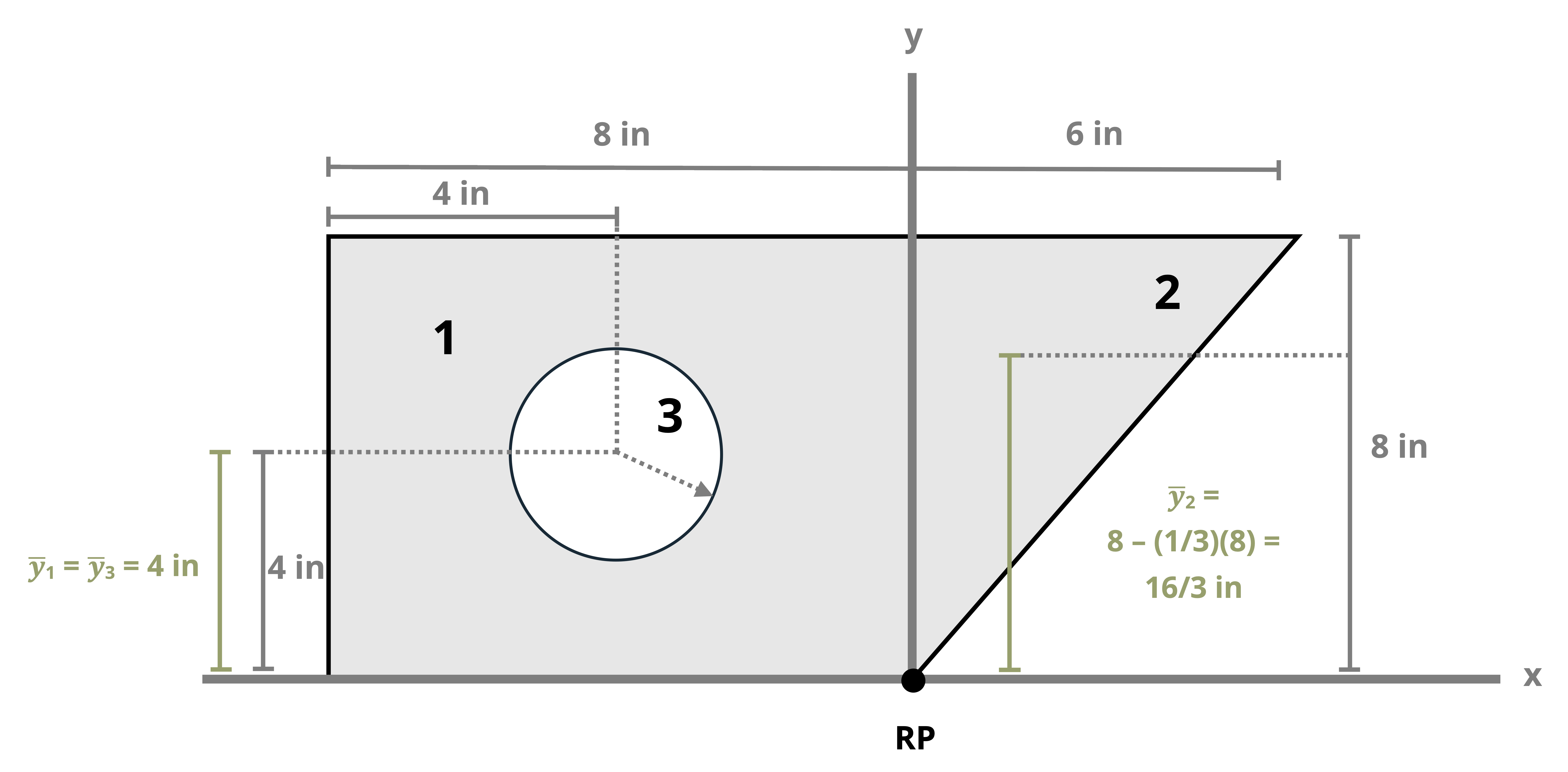

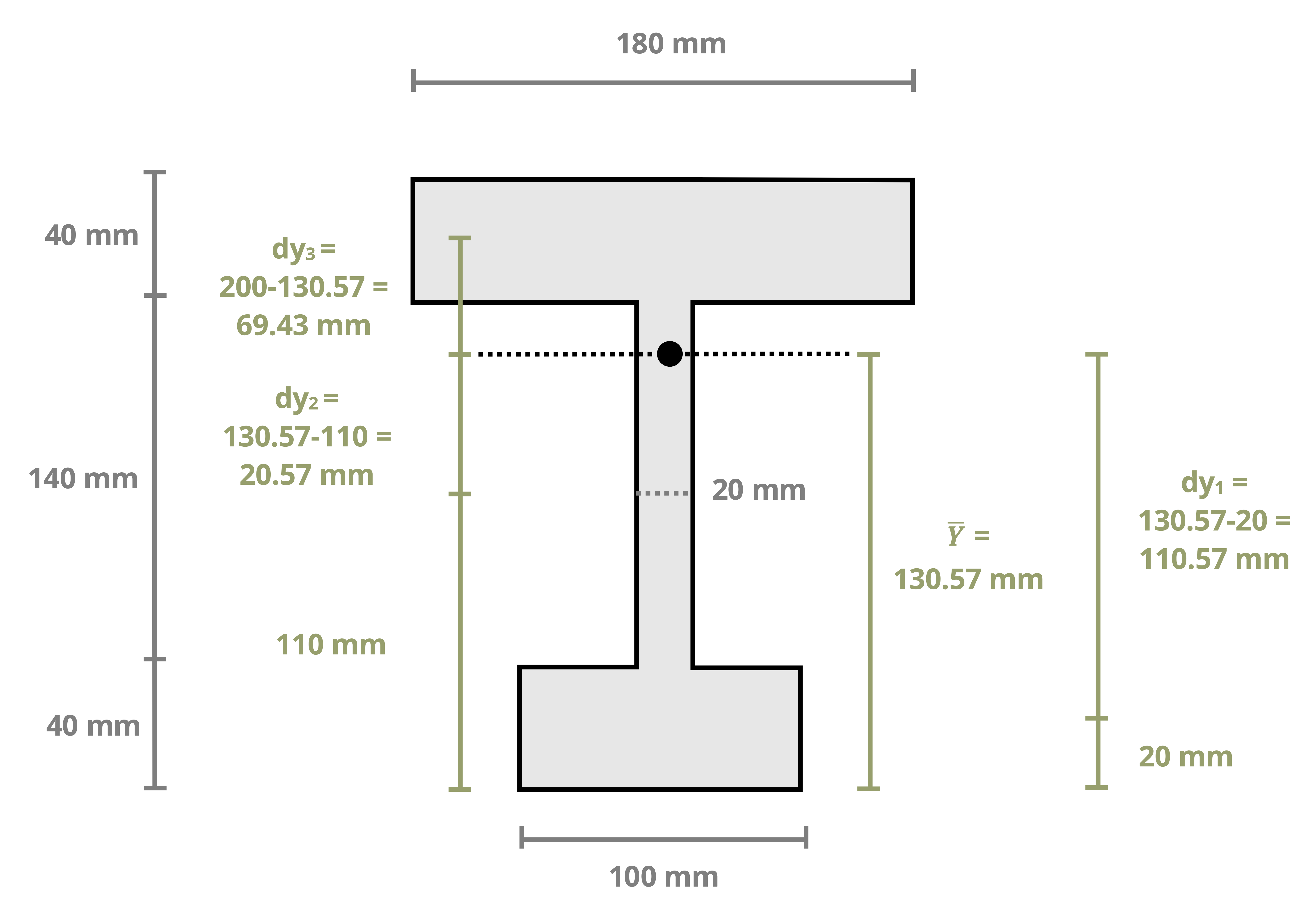

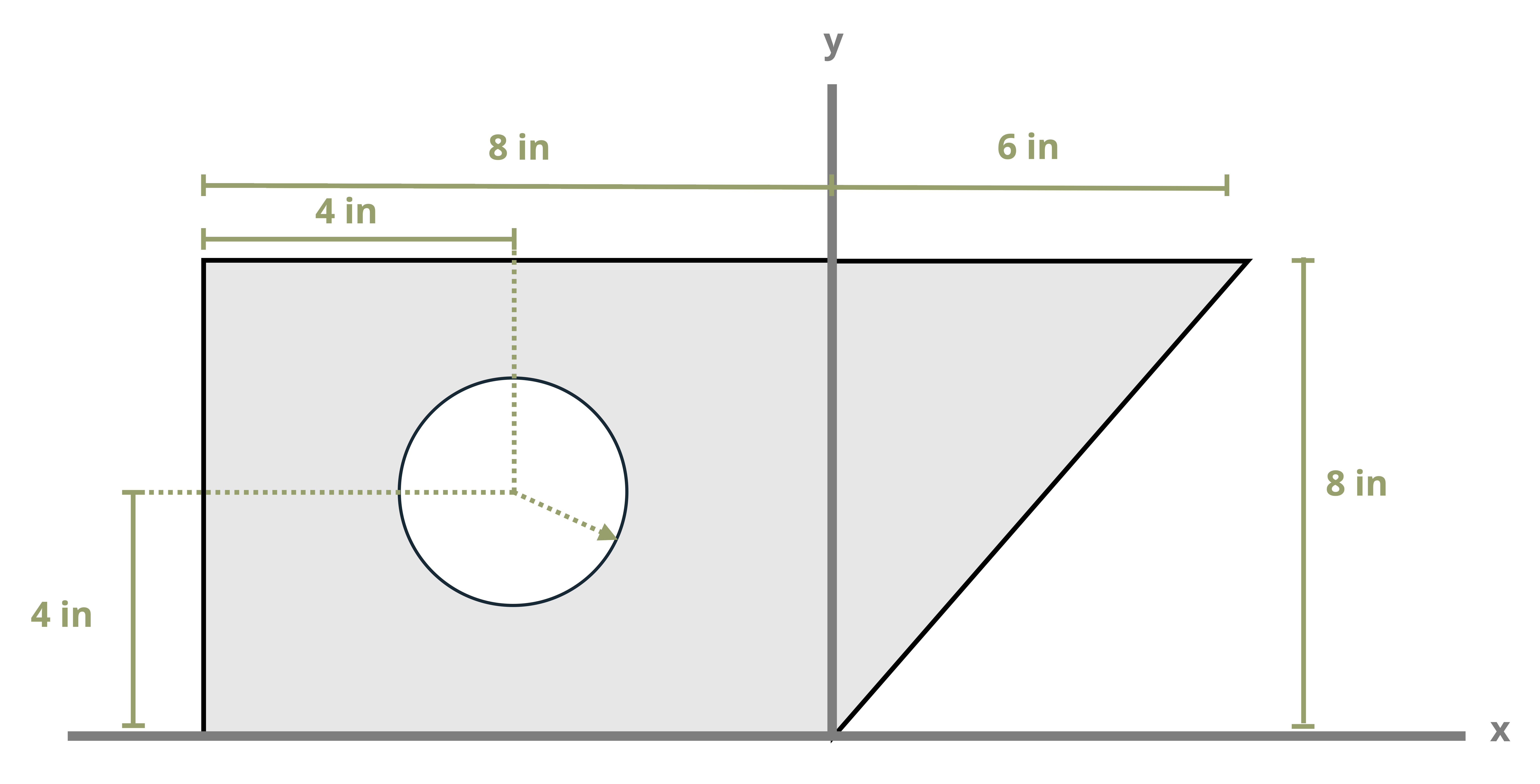

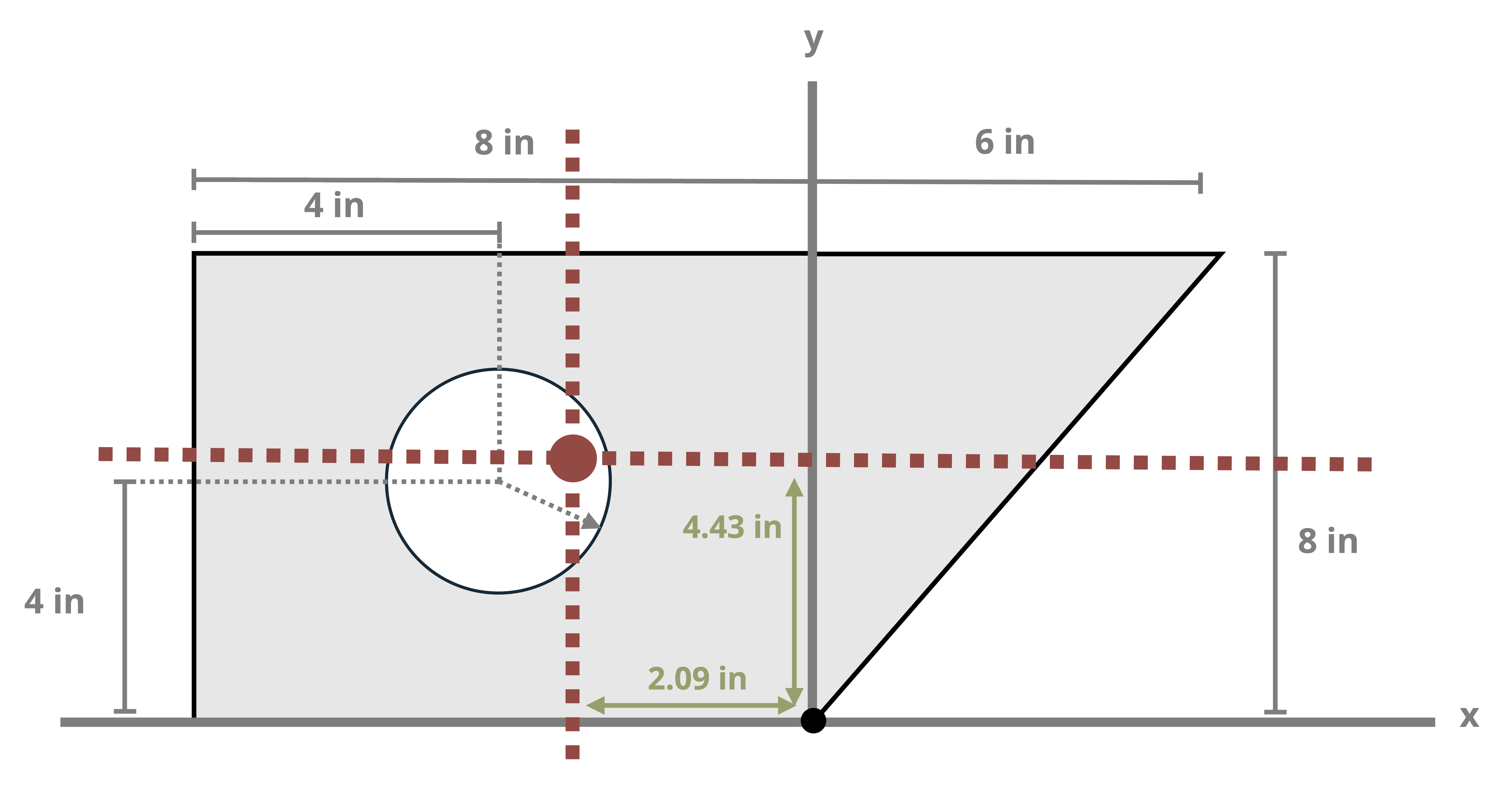

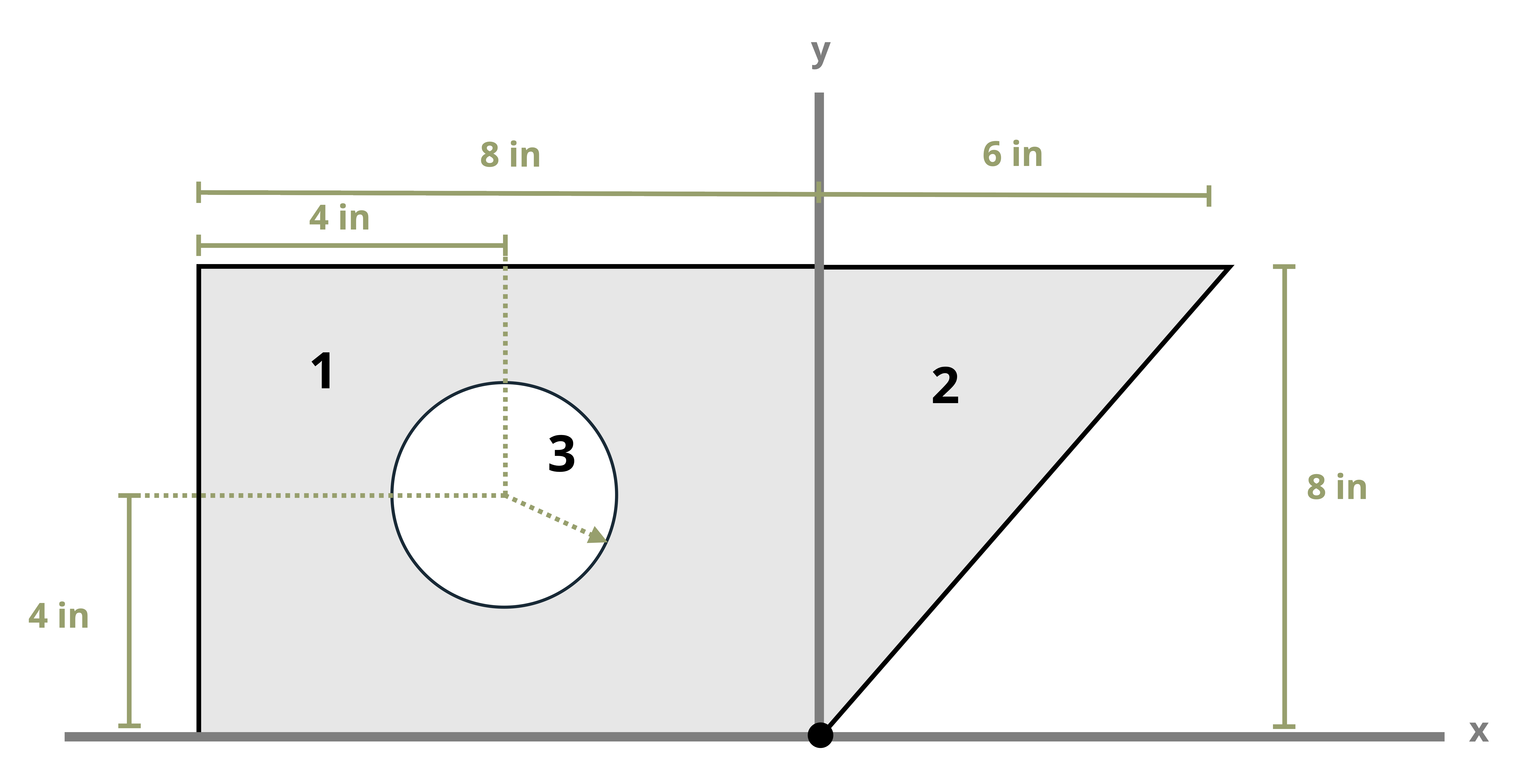

Example 8.1, Example 8.2, and Example 8.3 demonstrate the process for determining the centroid coordinates of composite areas.

8.2 Second Moment of Area

Click to expand

Another important geometric property needed to calculate stresses in beams is the second moment of area (also known as moment of inertia and area moment of inertia). You likely encountered this topic in statics, as you did the topic of centroids, so this section is designed as a review. By definition the second moment of area depicted in Figure 8.4 is

\[ \boxed{\begin{aligned} &I_x=\int_A y^2 d A \\ &I_y=\int_A x^2 d A \\ &I_z=J=\int_A r^2 d A \\ \end{aligned}} \tag{8.2}\]

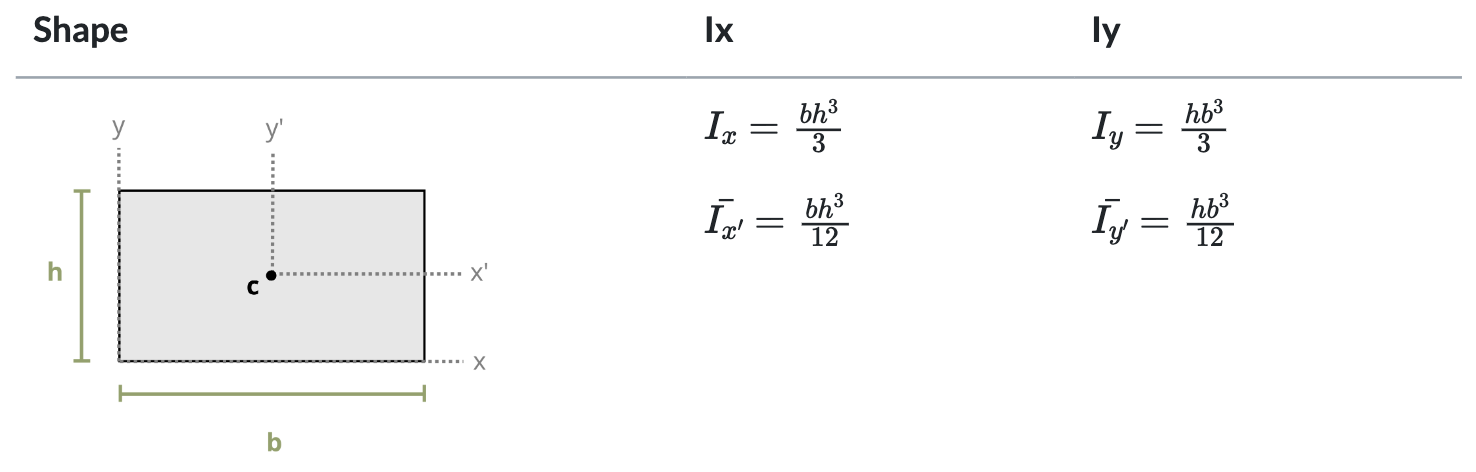

Keep in mind that this text uses common shapes or a composite of common shapes for cross-sections. Appendix E includes formulas to calculate the second moment of area. Part of Appendix E is reproduced in Figure 8.5. Each row of the table includes a common shape with the centroid marked and with formulas for determining the second moment of area about the centroidal axes x, y, and z. Note that these equations are valid only for the axes passing through the area’s centroid and are written as \(\overline{I_{x^{\prime}}}\), \(\overline{I_{y^{\prime}}}\), and J respectively. The bar notation is used to signify that the second moment of area is being calculated around the centroidal axes.

As noted previously, structural sections, called composite sections, are often combinations of these standard shapes. As with calculating centroids, we break these composite sections into common shapes and find the second moment of area of these individual shapes. When calculating each individual shape’s second moment of area, we must ensure that they are all about the same axis.

The parallel axis theorem provides a method for calculating the second moment of area about an axis parallel to an axis passing through the centroid, given that the second moment of area about the latter axis is known.

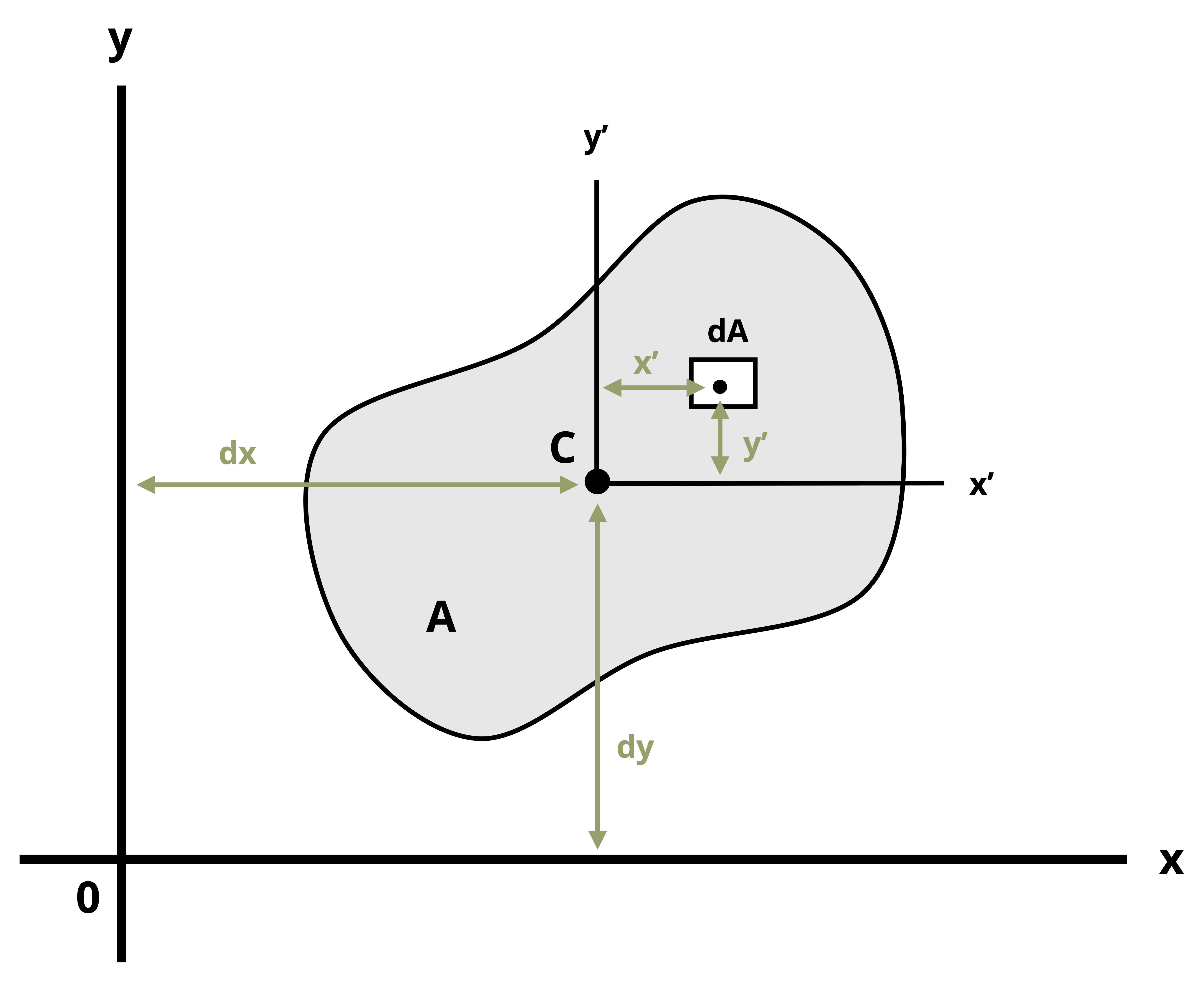

To establish the parallel axis theorem, we’ll next examine the second moment of area about A relative to an axis x, as illustrated in Figure 8.6.

The centroid of the area is at C, where the x’-y’ axis is drawn; note that x’ is parallel to x and y’ is parallel to y. The x-y’ axes will be termed the centroidal axes and are at a distance of dx and dy from the x-y axes respectively. The distance between the element dA and the x’-axis is denoted as y’. The result is \(y=y^{\prime}+d_y\). Substituting into Equation 8.2 yields

\[ \begin{aligned} & I_x=\int\left(y^{\prime}+d_y\right)^2 d A \\ & I_x=\int\left(y^{\prime}\right)^2 d A+2 d_y \int y^{\prime} d A+d_y^2 \int d A \end{aligned}\text{ .} \]

The first integral represents the second moment of area about the centroidal axis x’. The second integral is zero since the centroid is located on the x’-axis (i.e., \(\int y^{\prime} d A\) represents the first moment of area about the x’ centroidal axis, which is zero, as discussed in Section 8.1). The last integral represents the total area, A. So the resulting equation is

\[ \boxed{I_x=\overline{I_{x^{\prime}}}+A d_y^2}\text{ .} \tag{8.3}\]

A similar process is used to find an expression for Iy.

\[ \boxed{I_y=\overline{I_{y^{\prime}}}+A d_x^2}\text{ ,} \tag{8.4}\]

Ix, Iy = Second moment of area with respect to a given axis [m4, in.4]

\(\overline{I_{x^{\prime}}}\) , \(\overline{I_{y^{\prime}}}\) = Second moment of area with respect to a parallel axis passing through the centroid of the area [m4, in.4]

A = Area [m2, in.2]

dx, dy = Perpendicular distance between the given axis and the parallel centroidal axis [m, in.]

While the parallel axis theorem can be used to calculate the second moment of area around any pair of axes, here the focus is primarily on calculating the second moment of area around the centroidal axes of a composite region (this is this term used in Chapter 9 and Chapter 10 when calculating bending stresses and shear stresses). Example 8.4, Example 8.5, and Example 8.6 demonstrate using the parallel axis theorem to find the second moment of area for the composite areas from the earlier examples about their centroidal axes.

Summary

Click to expand

References

Click to expand

Figures

All figures in this chapter were created by Kindred Grey in 2025 and released under a CC BY license, except for

- Figure 8.1: Isometric view of concrete barriers used in roadway construction. Pushcreativity. 2008. CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Concrete_step_barrier_3D_cross_section.jpg.